Bandura developed a reciprocal determinism model for Social cognitive theory that consists of three main factors: behavior, person/cognitive, and environment (Santrock 2011). His theory states that environmental factors and observational will influence learning. The model can be considered cyclic, in a Person-Behavior-Environment loop: environment influences the person's cognition (expectations, beliefs, attitudes, strategies, thinking, and intelligence), which is reflected in their Behaviour, which causes an effect on their environment, which again influences the person. The cycle can also be describes in reverse. This model differs from Classical Conditioning and Operant Conditioning in that the conditioning of classical and Operant tend to be purposefully enforced on the learner. Classical conditioning uses triggers to condition the learner into a behaviour, and Operant Conditioning the consequences of behavior produce changes in the probability that the behavior will occur. Both models are considered methods "used" on a learner. The Bandura model takes into account everything used and not used around the learner to influence their social cognition.

For example, a child may engage in Response disinhibition if they observe that, though they were scolded for taking a cookie without asking their sibling got away with the same behaviour, the child may actually engage in the cookie-stealing behaviour more often.

A child may display Response inhibition, or, engaging in a previously learned behavior less often if they see someone get punished for it. To paint a traumatic example, if a child learns to roller-skate on Tuesday but on Wednesday observes a friend get pushed over by a bully while roller-skating the child may engage in their learned behavior (skating) less.

A common example of how modeling effects learning is Observational learning. A child sees a behavior and mimics it, such as a toddler clapping when an adult claps at it, or a teenager learning how to reproduce circles with a compass in Geometry class. According to Bandura there are four key processes to observational learning: Attention, Retention, Production, and Motivation. In Attention a child sees or pays attention to the model of behaviour, usually their parent. The model is influenced by their own affective output such friendliness, grouchiness, laziness, etc. To reproduce the model's behaviour the child engages in Retention; they code the information and keep it in memory so they can retrieve it (Santrock 2011). The more vivid or engaging the behavior the more likely it is to be retained. Though the information is coded the child may not be able to produce the behaviour (especially if the behavior is throwing boulders around like Superman). For realistic models, like throwing a basketball instead of a boulder, practice and coaching from a model can improve Production of the behaviour. Last in the Observational Model is Motivation. The learner may not be motivated to produce the modeled behaviour (see the teen and his Geometry circles above). Subsequent reinforcement of the behaviour, or incentives like report cards, can supply the motivation to imitate the model's behavior.

Self-efficacy is the belief that one can master a situation and produce positive outcomes. It is not motivation, per say, but can be a source of motivation. Self-efficacy is cognitive-domain-specific and should not be confused with self-esteem, which can apply to a wide variety of activities (Willems 2013). Self-efficacy effects learning and achievement in that a child with high self-efficacy and believes they will do well on a test may be motivated to try their best to achieve that, or an even better, grade. A child low self-efficacy might not even try to study for a test because they don't believe it will do them any good (Santrock 2011). To use an academic example, if a student has low self-efficacy and thinks they just cannot "get" reading they may be less likely to even open the book. If they were to have their self-efficacy increased, maybe through some positive feedback from a teacher or parent, the child will be more likely to try. A child with high self-efficacy has probably already read the book, just to prove to themselves how awesome they are. To a certain extent self-efficacy can be influenced by environmental modeling (viewing of others successes and failures) and persuasion; helping to raise the self-efficacy of a child to the high level of the book-devourer should be a goal of every educator. In the classroom a teacher can help to increase a student's sense of self-efficacy through positive modeling and prosocial behaviors such as voluntary behavior intended to benefit another.

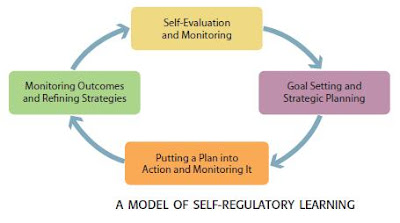

According to Santrock succinct definition, Self-regulatory learning consists of the self-generation and self-monitoring of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in order to reach a goal. These goals might be academic (improving comprehension while reading, becoming a more organized writer, learning how to do multiplication, asking relevant questions) or they might be socioemotional (controlling one’s anger, getting along better with peers) (Santrock 2011). Learners with a well developed sense of self-regulation set goals for themselves and are aware of emotional factors that may conflict with these goals, such as getting "stressed out" and taking a walk or stepping away from the frustrating activity. Educators can help students to become more self-regulated by giving them opportunities to be so. In 1996 Sebastian Bonner and Robert Kovach published a model to help low-self-regulatory students increase their self-regulation. In this multistep cycle the student engages (probably at the behest of an educator or mentor) in self-evaluation and monitoring by keeping a log or diary of their activities. These logs provide a record of what "worked" and "didn't work" at the end of their activities. With the help of a teacher the student sets a goal and outlines a plan to achieve it. A teacher can help the student break their goal into components or bite-size pieces and provide strategies to reach those goals. The student then goes about these strategies and continues to monitor their actions and progress. At the next conclusion the student again sees what "worked and didn't work" and this time achieved some or more of their goals. The cycle continues until the student no longer needs educator assistance in providing strategies and has become self-regulated and thereby more independent, confident in their abilities, and with a higher self-efficacy!

Santrock, John W. (2011) Educational Psychology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Willems, Patricia. (2013) Social Cognitive Theory (Slides). Retrieved from www.Blackboard.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment